The squat is the king of all exercises but the deadlift is the purest test of total-body strength. The deadlift primarily focuses on the musculature of the back, hips, and legs while recruiting just about as many muscles as any other exercise. The concentric-only nature of the deadlift is unique to the powerlifts because the squat and bench press both afford the lifter an opportunity to lower the bar first before actually lifting it. Without the eccentric phase, it’s nearly impossible to generate any momentum and stretch reflex utilization is practically non-existent. A belt, knee sleeves, suits, and wraps offer the least ergogenic aid in the deadlift. Accordingly, one’s performance in the deadlift is largely determined by three factors: genetics, technique, and training.

Genetics (Leverage)

As with all athletic endeavors, genetics play a major role in aptitude and performance. The most favorable physical attributes for the deadlift are a short torso, long arms, and long legs. Lamar Gant possessed all three traits in addition to having severe scoliosis which helped him become the only person to deadlift over five times bodyweight in two weight classes. The torso acts like a lever and does the lion’s share of the work. A shorter torso makes for a shorter moment arm while longer thighs creates a higher pivot point at the hips. Long arms simply decrease the distance of bar travel from the floor to lockout. A deadlifter’s physique is mostly opposite to the desired characteristics for squatting and bench pressing. Longer arms and legs usually translate to more work being done. But, in the case of the deadlift, longer limbs actually mean a more efficient movement.

Technique

The powerlifts should be viewed as movements executed rather than muscles used. Executing deep barbell squats, paused bench presses, and locked out deadlifts with significant weight requires kinesthetic awareness and skill. Any klutz can use their muscles for curls. At SSPT, it’s never a leg, chest, or back day. It’s squat, bench press, and deadlift day.

SSPT lifters don’t exercise. They train because training is our practice. After all, strength is a skill and skills are refined through extensive practice. Consistent, quality, and repetitious practice leads to technical mastery. Therefore, technique is the single most important factor in acquiring and performing a skill. Without solid technique, skill acquisition and strength development takes longer thereby forcing one to rely more heavily on genetics and ergogenic aids.

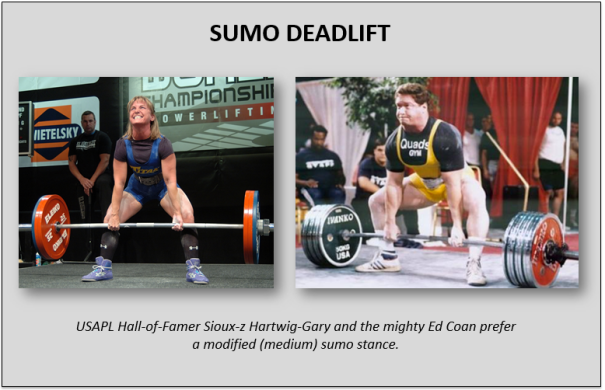

Developing appropriate deadlift technique should be largely based upon one’s anthropometry. Limb and torso length usually determine how you’re going perform the deadlift. The most perceivable aspect of deadlift style is stance. Deadlift stance is expressed across a broad continuum with frog-style, conventional stance pullers like Lamar Gant and Vince Anello at one end of the spectrum and ultra-wide, sumo lifters like Eric Kupperstein and Wei-Ling Chen at the other. Most of us fit somewhere in between.

I’m frequently asked about my preference for foot placement. My stock reply is, “I’m not married to any stance other than the one where you can lift the most weight.” Lifters tend to place their feet where they’re most comfortable. When a lifter is in a comfortable position, they typically move more proficiently. It’s incumbent upon the lifter to experiment with both styles and see what works best for them according to their leverages.

The default deadlift stance is conventional because it resembles the “athletic position” which translates better to most activities and sports. The athletic position is approximately shoulder or hip width. You see it all the time in baseball, basketball, boxing, football, and tennis to name a few. I coach my conventional stance deadlifters to stand where they would for a vertical jump test. This is routinely the place where most people are able to generate and transfer the most force into the ground. When using a conventional stance, the toes are pointed out slightly while the hands are placed just outside of the legs thus elongating the arms.

A sumo (wide) stance deadlift, with the feet placed outside the body, is irrefutably more efficient by shortening the distance of bar travel. However, what one gains in efficiency they often lose in force transfer. This is also seen with wide-grip benchers who struggle to get the weight moving off the chest or the wide-stance squatters who grapple with hitting depth and coming out of the hole. Sumo deadlifters are routinely slower from the floor and then accelerate through to lockout whereas the conventional style is usually opposite.

Powerlifters should opt for the stance that enables them to lift the most weight. Regardless of one’s preferred stance, body position is vital. Four crucial criteria must be satisfied to ensure the proper start position in the deadlift:

- The bar must be placed over the middle of the foot. This isn’t the part of the foot you can see when you look down but rather the mid-foot. Typically the bar needs to be about one to two inches away from the shins depending upon the length of the foot, height of the lifter, and hamstring flexibility.

- The arms must be kept straight and locked in extension.

- The back should be held in rigid extension and as flat as possible. Slight thoracic kyphosis (rounding) is acceptable provided the lifter maintains intra-abdominal pressure and tightness throughout the torso.

- The scapulae (shoulder blades / armpit crease) must be directly over the bar.

The photo (seen below) illustrates the proper start position for the deadlift. Notice how the arms, thighs, and back form a triangle. Each person’s triangle varies based upon his or her own unique structure. Longer thighs lead to a higher hip position while shorter arms lead to a more forward or horizontal torso. Regardless of what your triangle looks like, the hips will be in the correct spot as long as you satisfy the four, all-important technical standards. If you’ve never been in this proper start position before, your hips will feel abnormally high. But I can assure you; they’re exactly where they’re supposed to be. In fact, a properly executed deadlift will feel like a shorter movement due to the vertical-only bar path.

Neglecting any of those technical principles will significantly compromise the movement and lead to decrements in performance. A slight, initial rise of the hips, at the start of the pull, is not in and of itself a technical flaw so long as you’re in the correct start position. Hip rise is frequently a sign of not being tight enough. Just remember that maximal attempts won’t always look like ballet and things do tend to break down. This isn’t the end of the world but we should all train with the goal of becoming as strong as possible and therefore delaying the onset of form breakdowns. The longer you can hold your optimal position during a max attempt, the better off you’ll be.

Oftentimes improper bar and shoulder placement give way to both hip rise and horizontal bar displacement in what should ideally be a vertical-only lift. This horizontal movement known as “hook” is an unwanted technical inefficiency. Sumo deadlifters are famous for this when trying to squat the weight up. Occasionally you’ll hear one quip, “The deadlift is just a squat with the bar held in front of you.” Don’t believe this fallacy. The deadlift is not a squat. Oppositely, the deadlift is a hip-hinge movement with the ultimate goal of the bar and hips meeting in the finished position. While the squat is a leg-dominant movement assisted by the back, the deadlift is a back-dominant movement assisted by the legs. Much is different between the squat and deadlift including bar placement, hand position, stance, center of gravity management, muscle contraction sequencing, and the degree of knee and trunk flexion vs. hip extension. As a result of these differences, it’s reasonable to approach deadlift training differently than the squat or bench press.

Training

Like the squat and bench press, deadlifting is a skill. Only a heretic would advise not deadlifting as the optimal means for building a bigger deadlift. That’s like telling a world-class violinist to spend their time practicing on the tuba. If you want to deadlift more, you should deadlift more.

The two primary ways of training the deadlift are with multiple repetitions or singles. And while there are examples of world-class deadlifters using the multiple reps approach, at SSPT, we much prefer singles and for good reason.

There’s an old deadlift axiom that says, “If you can hit it for one rep, you can probably do two.” This is the direct result of using stored elastic energy on the eccentric portion of the start of the second rep. Lowering the weight first enables us to build tension, generate momentum, and employ the stretch reflex. Even if you perform multiple repetitions in a “dead-stop” fashion, the successive reps are still easier because of the tension you’ve built on the eccentric phase of the preceding reps.

Multiple-rep sets of deadlift are more appropriate for bodybuilders, fitness enthusiasts, strongman competitors, and other strength athletes who want to put on some muscle and/or increase their muscular endurance. More time under tension may help your muscles grow but, for powerlifters, our singular objective is lifting maximum weight. In terms of deadlift training for a one-rep max, singles are more optimal.

On numerous occasions I have seen lifters perform heavy doubles or triples in training and then barely be able to complete their attempt at the meet with the same weight. This is especially true of those who bounce or use a “touch n go” style. This enables trainees to use energy from the floor to assist in lifting the weight. At competitions, all deadlifts begin motionless from the floor so the multiple reps approach is irrelevant in terms of building momentum at the start. Furthermore, multiple-rep sets arguably lead to greater degrees of fatigue and higher susceptibility to injury. With multiple reps, lower back fatigue eventually becomes a limiting factor resulting in technical breakdowns.

Performing singles in the deadlift doesn’t mean coming into the gym, loading the bar to your maximum weight, pulling it once, and going home. Deadlift training requires a planned and systematic approach of using percentages for multiple singles then attacking the muscles that are germane to the movement. An additional benefit to training the deadlift with multiple singles is more practice.

Powerlifting may be the best example of a “practice like you play” sport. Lifters should strive to simulate meet conditions in training as often as possible and singles afford you that opportunity. Singles allow you to treat each rep as its own attempt or set. You can practice visualization, set-up, breathing, and technique with each one. With multiple-rep approaches, you only get one shot on the first rep of each set.

For example, let’s assume Lifter A deadlifts 440-pounds (200kg) for one set of 10 reps. This equates to a total training volume of roughly 4,400-pounds (2000kg). Odds are high that the lifter exerted tremendous effort during the set and the last few reps probably looked pretty ugly due to accumulated fatigue and subsequent technical breakdowns. Such a Herculean effort would likely require a long rest period before an additional set was attempted. On the other hand, Lifter B performs 10 sets of 1 rep with the same weight. The total training volume is identical but Lifter B was afforded 10 times as many opportunities to practice their sport-form skills of setting-up, breathing, and executing the lift to standard. Short rest periods between reps enabled Lifter B to regroup, perhaps chalk their hands, and reset before the next rep. Furthermore, each rep was a first rep that wasn’t influenced by momentum or the stretch reflex. Performing ten “first” reps increases skill acquisition and the likelihood of enhanced technique. Stop looking at volume like endless toil and start seeing it through a different lens. Be thankful for the additional opportunities to improve and sharpen your skills.

It’s difficult to generate momentum in the deadlift because we must overcome inertia on the bar. You’re not apt to get a heavy weight moving from the floor by pulling it slowly. Deadlifts need to be done explosively with a focus on technique and speed. Singles allow you to be explosive and deliver maximum force into the barbell each time. Multiple repetitions do not allow the same velocity because as the set continues, bar speed significantly decreases with each repetition. As form breaks down over the set, the risk of injury may increase and you’re not likely to be in the correct start position again after the first rep. This is not the preferred combination and doesn’t set the table for an optimal training environment. Moreover, singles allow you to train the deadlift more frequently and at higher intensities. Muscle damage is reduced and greater loads can be used. Increasing frequency and intensity helps bridge the volume gap created by doing one rep per set as opposed to multiple reps.

It’s all about skill acquisition. Here’s a look at three sample 10-week plans featuring varied frequency, intensities, and volume:

The above plans are linear from week to week. With the first option, you may add some back down (fatigue drop) singles in the latter weeks to accommodate for the reduction in volume but it’s not always necessary. The second two examples place the heaviest deadlifts earlier in the week. That can be switched to meet your schedule and/or create a different undulation. Our long-term planning is more undulating in nature with the majority of our training occurring in the 80-89% range. There are enormous benefits to hovering around that intensity. It’s light enough where one can perform lots of volume to acquire skill without overtraining or needing a deload. On the other hand, it’s heavy enough to elicit a significant strength response and keep lifters close to top form. When 80-89% is your home base, you’re never very far from bringing your strength to a peak. You can create your own training plan using SSPT’s Deadlift Table. The options are infinite.

We train like we compete so most training sessions begin with squats and we always squat before deadlifting. The squat serves as a warm-up for the deadlift and prepares us for the rigors of game day. When using the once/week option above, the deadlifts are performed after a high-volume, medium-intensity squat. Later in the week, we’ll squat heavy immediately followed by a special deadlift assistance exercise based on our individual weaknesses. You’ll rarely see anyone at SSPT deadlifting with the opposite grip or stance. Our specific deadlift assistance exercises closely resemble the competition style deadlift and are most often trained in the one to three rep range but sometimes as high as four or five. We may select from deficit, halting (pause), rack/block (partials), Romanian deadlifts, or even add chains. These assistance deadlift moves are typically implemented via Rates of Perceived Exertion (RPE) or percentages (of our DL max) for three to four consecutive weeks over the course of a single training block. After using a special exercise for one block, we’ll switch it for another. Training sessions are occasionally finished with a non-specific (supplemental) posterior chain movement but always with some direct (weighted) abdominal work.

Most of our cycles end with our final heavy deadlift about 10-14 days out from a meet. For those worried about losing skill over the final week, rest easy. You’re not going to magically forget how to deadlift overnight. Your body will supercompensate and thank you for the additional rest. You want to head into the meet with a ravenous attitude. There’s nothing worse than feeling overtrained and leaving your heaviest deadlift in the gym. You do not need to test (max) the deadlift in training to hit a personal record (PR) at the meet. Most of our competition (peaking blocks) preparation ends at roughly 95% of our max. The deadlift is the powerlift most affected by game day adrenaline. Rest assured if your 95% singles go smoothly in training, you’ll be good for significantly more at the meet. Even our second attempts in competition are often heavier than our final heavy single in training and they are always faster.

In preparation for the 2014 USA Powerlifting Raw Nationals, my final heavy single in training was 567-pounds (257.5kg) on Monday, July 7. On Sunday, July 20, I nailed 573-pounds (260kg) on my second attempt en route to an all-time beltless PR of 600-pounds (272.5kg) on my third. The PR was never in doubt. Starting months in advance, I visualized and performed it hundreds of times in my mind before ever stepping on the platform. I always use a winning mental approach because attitude is everything. On game day it all boils down to attempt selection and execution. Everything else is trivial and you’ll never find me on Facebook or Twitter between attempts.

The great Greek philosopher Aristotle said, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” Focus on the process, commit to consistency, and strive for technical mastery. The results will take care of themselves. You may not break a world record but with a single rep at a time; you can become an excellent deadlifter.

[…] last few months of training have been a mix of Wendler’s 5/3/1 and SSPT Deadlift training. Both these programs are fairly low volume, which seems to work very well for […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never seen the frog stance before, going to have to try that out, even though typically I stick with a conventional stance. I know you said that you don’t have a preference, but does body structure come into play at all? Thanks.

LikeLike

Yes, I could assure body structure do have a big influence in one’s preferred stance/style. Previously I’ve been deadlifting with a neutral stance, toe slightly out, kind of a standard conventional form, but I often can’t feel the push from my legs upon execution, and even if i put the bar over my midfoot, the bar hardly able to attach at my shin and I can’t push through my heel well during the lift.

Few months later, I experimented my own body with just standing straight or walk naturally, and I found that my foot actually tends to angled out more than others do (like a 2 o’clock direction). In another word, if you look from the front, my foot feels like not walking in a straight path. So later I tried deadlifting in the 2 o’clock direction, which is the frog-stance position, and it immediately fixed my problem! I can feel the push from my quads – firing right from the bottom. The bar is so attach to me the entire lift, and certainly, I can deadlift more than I ever did, with lesser fatigue. My form has never been so perfect until I made such alteration. My advise to you is to find out how your body naturally operates, then lift according to your built. You can’t immitate other people to your built, you should lift what’s best for your own. Hope this helps.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on kompoundfitness.

LikeLike

Kudos! A good amount of postings.

LikeLike

I agree! I also had some readers asking me why they found no results from their program only to find out that they are powerlifters and they train to failure..

I explained that failure is specific to achieving time under tension for the purpose of acquiring sarcoplasmic hypertrophy.

However it is interesting those different foot placement. Let me ask.. since I am not a powerlifter I am not familiar with the rules, is there a specific rule regarding meets that one needs to – for example – employ a standard stance, or are there meets where they won’t allow you to do sumo stance deadlifts?

And furthermore is there a generic calculator to determine what type of stance will you best be in deadlifts? I don’t know if my arms are long etc.

cheers!

LikeLike

I fail to see my comment here, was it spammed?

heres my comment:

I agree! I also had some readers asking me why they found no results from their program only to find out that they are powerlifters and they train to failure..

I explained that failure is specific to achieving time under tension for the purpose of acquiring sarcoplasmic hypertrophy.

However it is interesting those different foot placement. Let me ask.. since I am not a powerlifter I am not familiar with the rules, is there a specific rule regarding meets that one needs to – for example – employ a standard stance, or are there meets where they won’t allow you to do sumo stance deadlifts?

And furthermore is there a generic calculator to determine what type of stance will you best be in deadlifts? I don’t know if my arms are long etc.

LikeLike

[…] hit the 3 singles next Monday, and confident that I'll hit a significant PR the following week): SSPT Deadlift Training | Maryland Powerlifting The Champagne of Beards Reply With […]

LikeLike

[…] of I'm following the sspt linear cycle, not completed it yet but momentome is good SSPT Deadlift Training | USA Powerlifting MARYLAND Reply With Quote […]

LikeLike

Hey,

Thank you a lot for this epic and detailed article. I have written a post on 5 Valuable Types of Powerful Deadlift Exercises that based on yours.

Again, thank you for your help.

LikeLike

Singles training works as great for grip strength; I’ve just hit my first 300-lb snatch-grip deadlift without straps (grip about 2 inches outside the rings). As opposed to using heavy grippers, doing something like one-handed Dumbbell Deadlit for singles (as I write this, I’m doing 15 easy singles with 154 lbs) doesn’t take away from other lifts.

LikeLike

Anyone know what the recommended rest period between singles is?

LikeLike

It’s typical 1 minute rests THOUGH if you require more rest so that you don’t sacrifice form then take it up to 5 minutes rests between singles. Also, obviously the higher weight during the end of a cycle the longer your rests will become between sets. I like to start my cycles with EMOM (every minute on the minute singles) rest between singles and as the weight grows heavier later in the cycle add an additional 30 seconds of rest to accommodate for fatigue but never going over 5 minutes rests between singles. ALWAYS REMEMBER that you should NEVER sacrifice form. If you need more rest to ensure the next rep is performed properly then take it. Lifting is not a sprint, it’s a life-ling marathon.

LikeLike

Can someone recommend Accessories? Cheers xxx

LikeLike